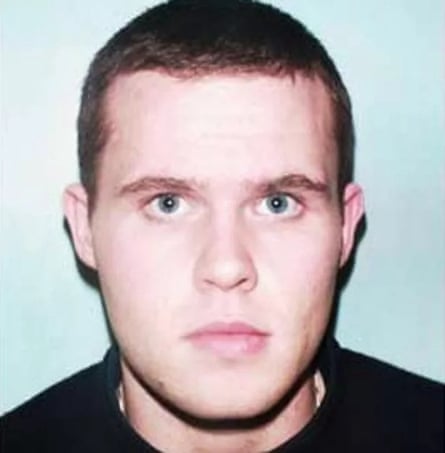

John McAvoy sat in a holding cell in Belmarsh prison, waiting to be processed, plotting his escape. It was 2007, he was 24, and he had been arrested for firearms offences and conspiracy to commit robbery. He knew he was facing a long stretch inside, having previously served three years for possession of a firearm. He also knew his only chance of running was through the hospital wing, so had spent the day lying to guards, pretending that he had sustained a concussion during his arrest. When the holding cell doors opened, he figured that’s where he was going. Instead, he was cuffed and led away to a high-security unit (HSU).

When McAvoy laid eyes on the unit, the magnitude of his situation hit home. “I thought: ‘I’m not going to see daylight for a long, long time.’”

The Belmarsh HSU is a prison within a prison. Getting there requires a short drive on a bus through the main prison, beyond a dedicated gate and perimeter wall. There’s an airlock where door locks were operated remotely to prevent hostage taking. The spur on the HSU is small, with around eight cells, low ceilings and fluorescent lights. “We used to call it the submarine,” recalls McAvoy. “There’s no real natural sunlight. One of the wings hasn’t got any windows at all. It’s very, very claustrophobic.” There was an exercise yard, but the sky was blocked out by security wire. McAvoy’s fellow inmates included the radical preacher Abu Hamza and the failed 21/7 bombers.

“This is the end of the world,” one of the prison governors told him. And it really could have been. But for McAvoy it was a beginning: the first unlikely step toward becoming the prolific endurance athlete he is today. By the time of his release in 2012, after spending nearly a decade of his life inside, he had broken three world records and seven British records in rowing – all from the confines of the prison gym.

McAvoy was born in London in the early 80s, and he and his sister were raised by his mother and five aunts. He never knew his biological father, who died a month before he was born. McAvoy’s mother worked as a florist. They didn’t have much money, “but she did everything she could to make sure her two children had everything they ever needed”. McAvoy was an energetic boy, sometimes naughty. His childhood home backed on to Crystal Palace Park in south-east London, where he’d make camps with his friends and poach fish from the lake.

When McAvoy was eight, his mother brought home her new partner, Billy Tobin. Aside from the odd uncle or cousin, Tobin was the first permanent male presence McAvoy had had at home. Tobin was an armed robber. Not that McAvoy knew that at the time; he just found him intoxicating. He remembers Tobin’s charisma, his shiny black shoes, dark trousers and shirt. “Even though I was young, I could tell the stuff he had on was very expensive.” When Tobin went to say goodbye that day, he patted McAvoy on the head, called him a good boy and gave him a £20 note (the first time McAvoy had held paper money). Tobin became McAvoy’s stepfather soon afterwards. “It was just a really powerful experience.” McAvoy was a driven teenager, full of ambition. “I grew up in the era of Margaret Thatcher. It was all about the ‘me’. I wanted to own British Telecom. I wanted to be a billionaire.”

As he got older, McAvoy became aware of more criminal notoriety in his family tree. His uncle Micky McAvoy was part of the gang arrested for the Brink’s-Mat heist – one of the biggest robberies in British history, in which £26m in gold bullion, diamonds and cash was stolen from a warehouse at Heathrow Airport. McAvoy was 12 when he saw Fool’s Gold, the 1992 TV film based on the robbery, in which Sean Bean played his uncle. “It was one of the big moments of my childhood,” he says, “Sean Bean sitting on £26m worth of gold bars and it all being glamorised.” It wouldn’t be long before he became involved in his stepfather’s criminal world – at 14, Tobin tasked him with watching duffle bags stuffed with £250,000 in cash on their kitchen table before someone came to collect it. He was paid £1,000 for the job.

When McAvoy was 16, he left school and bought a gun. Tobin was furious – he didn’t want McAvoy to do anything reckless. He confiscated the weapon and took his stepson under his wing. “I didn’t really have friends my own age,” he says. “From 15, I was with men who were in their 30s, 40s and 50s.” They were all wealthy criminals. “I spent as much time as I could around these people because I wanted to learn from them and I wanted to understand how that world operated.”

Tobin put McAvoy to work, tracking cash-delivery vans, scouting targets and passing information up the chain of command. McAvoy was a shy teenager who struggled to communicate, but Tobin taught him to be assertive. He also taught him to never trust women, never talk in houses because they might be bugged, and to only trust people in your circle. He told him to never show weakness – and to detest authority. Anyone in the system – the government, judges, the police – was viewed as the enemy. “There was always this tone of anti-authority and how corrupt the system was. Obviously, I didn’t realise I was absorbing all this stuff.” There was a strict code of conduct among them too: “You don’t hurt women, you don’t hurt children, don’t hurt old people.”

McAvoy knew that prison was a very real occupational hazard in his line of work. “I think it’s always in your subconscious but you think you’re going to be that one to live that Hollywood life, right? You’re going to be the one to sail off into the sunset.” He was being followed by police – he had found tracking devices on his car – and “was always very surveillance aware. You would sometimes spot the same person a couple of times.”

McAvoy’s first arrest came at 18, after police thwarted a robbery with an estimated value of £250,000. He led the police in a motorway car chase, dumped the car (along with his gun) in south-east London, stripped down to his shorts (he’d been told to always wear shorts so you don’t look out of place when running) and continued on foot. After vaulting garden fences, he thought he’d escaped. He found a phone box and called a friend, but was then swarmed by armed police and arrested. McAvoy was sentenced to five years for possession of a firearm. He served three, one in solitary confinement.

His second arrest came in 2005, two years after his release. Then 22, McAvoy was on his way to rob a security van carrying cash when he clocked an unmarked police car driving toward him. It was an ambush. The police had been investigating McAvoy and his associates for months. As armed officers spilled out of three police cars, McAvoy sped off, through the streets of south London.

“I just remember this internal dialogue in my head, thinking: ‘I’m not going back to prison.’ And, honestly, I was fully prepared to die in that moment to get away from them.” After mounting a pavement and hitting a lamp-post, McAvoy ditched the car and bolted on foot, determined to outrun the helicopter above. He hit a dead end. The police caught up. They locked their guns on him. “I genuinely thought at that moment, ‘I’m gone’,” he says.

McAvoy pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit robbery and one count of possession of firearms with intent to commit robbery. Three days later, he was transferred to Belmarsh.

McAvoy was given a discretionary life sentence. His uncle Micky, who did 16 years for the Brink’s-Mat robbery, gave him some advice: stay connected to the real world. “I always kept myself in the present,” he says. He’d listen to the radio and watch the news. “I never got involved in prison politics. I used to think: ‘This is not my life. I just want to get out of this place as quick as I can and get my life back.’”

He had one visit from his mum. It took a few weeks for the governor to clear it. She drove to the prison, then took the bus to the HSU, before sitting in a booth behind armoured glass. A prison officer sat behind McAvoy with a pen and paper. They weren’t allowed to speak in code, couldn’t cover their mouths, and there were cameras pointing at both of their faces. Abu Hamza was in the booth next to him having a legal visit. McAvoy was with his mum for 90 minutes. He clocked that it was a deeply traumatic experience for her. “I made a decision that day – I went back to my cell and she didn’t see me again until the day that I got out, nearly eight years later.”

At first, he couldn’t understand why he was on the same unit as terrorists. He expressed as much to a visitor from the Ministry of Justice, but was told they didn’t want to give him any opportunity to run. “You get seen as a piece of shit,” says McAvoy. “There was never any talk about rehabilitation or moving forward in life in a positive direction. It’s just like, that’s who you are, and that’s what you are, and that’s how you’re gonna stay for the rest of your life.”

McAvoy was, he says, goal-obsessed. He read diligently, and kept fit by doing what he called “cell circuits” – thousands of sit-ups, step-ups and push-ups. He was comfortable in solitude and never struggled with boredom. “I never had mental health [issues] in there,” he says. “I never allowed my mind to drift too far in the future.”

After two years in Belmarsh, he was transferred to Full Sutton, a maximum security prison in Yorkshire, before later being moved to Lowdham Grange, a category B prison in Nottinghamshire. At first, McAvoy’s goal was simple: play the game until he was moved into a low enough security prison, then abscond. “I thought the minute they give me an opportunity in a semi-open prison, I’m gone. And I’ll go to Europe, I’ll be living the lifestyle of a criminal. That was my mindset.”

Three years into his sentence, however, all that changed. A close friend, Aaron, died in a car crash in the Netherlands. He’d been attempting to escape after robbing an ATM along with a couple of associates. McAvoy saw CCTV of the incident on a news report the following night.

“That was the lowest I think I’ve ever been in my whole life,” he says. “It just made me have this massive reality check about my life and where I was and what I was doing.” It was a grim catalyst for change. “I felt lost. I didn’t know what I wanted to do and where I wanted to go. I was trapped in this physical environment and I needed to escape it. I needed to get away from the prisoners. I wanted my life to be something else than this.”

McAvoy went to the prison gym. He noticed another prisoner on a rowing machine, who’d had more than the usual allotted time in the gym. He enquired and the prisoner told him he was rowing 1m metres for a children’s charity. McAvoy asked the gym officer if he could do the same. That is how he started rowing.

“I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t know anything about technique. But when I was on that machine, it was like I created this portal that took me out of prison. Everyone left me alone. No one spoke to me. I was in my own thoughts and then it was like meditation. It was very rhythmical.” He suspects now that he’d discovered the runner’s high. “It was like the machine became an extension of my body.”

McAvoy did the first 1m metres in a month. He asked if he could do another sponsored row, and then another. Someone suggested he do the equivalent of rowing the Atlantic Ocean – 5,000km. “I thought it’d be quite a nice thing to do and to say I’d achieved.” One evening, as he was coming toward the end of his latest charity effort, he decided to pound through a really hard 10,000 metres. A prison officer, Darren Davis, took an interest in his impressive performance. “A couple of days later he came back and gave me all the records that were set on an indoor row machine.”

In just over a year, McAvoy broke three indoor rowing world records and seven British records. He smashed the fastest marathon by seven minutes, took the record for the longest continuous row (45 hours) and rowed the farthest distance in 24 hours (263,396m).

McAvoy hated Davis at first. He wasn’t interested in reform and saw the guard as an extension of the system. But Davis’s unwavering interest in McAvoy’s performances won him over. “He saw that I had that talent and he put that belief in me that I could achieve something else in my life.” Davis was present for all of McAvoy’s record-breaking efforts inside. He’d pull up a chair and sit with him. If McAvoy was doing a 24-hour row, Davis would take the day off, come in and stay with him the whole time, coaching him.

“He changed my life in prison,” says McAvoy. “He wanted to help me for no other reason other than wanting to help me. There’s nothing in it other than the purity of a human that wanted to do something for someone else without anything in it for themselves.”

Today, Davis is one of McAvoy’s best friends. “I knew when my friend died I would never commit a crime again, and I don’t know where that road would have taken me,” says McAvoy. “But I wouldn’t have the life I’ve got today unless Darren believed in me, then gave me the opportunities to use the gift that he saw I had.”

McAvoy started studying for a personal trainer qualification in prison. When he was moved to Sudbury, a category D prison, he got a job as a trainer at a Fitness First gym. He’d catch a 7am bus from the prison, six days a week. In between training clients, he studied endurance athletes. Nine months later, in 2012, he was granted parole and released from prison. Just under eight years had passed since his second conviction. The first thing he did when he left prison was visit the grave of his friend Aaron.

McAvoy had one goal: to become a professional athlete. At 30, he knew time wasn’t on his side, so he began training for a triathlon: he joined a rowing club, taught himself to swim via YouTube, bought his first bike and learned to ride. He’s since established himself as a formidable endurance athlete, running numerous ultramarathons, triathlons and Ironman events.

“Being in prison and being in solitude and isolation for years, it definitely shaped me as an athlete,” he says. “I’ve been in a segregation cell … Everything else now to me is a privilege. It’s a luxury.”

The race that stands out most to him is his Ironman debut in 2013, in Bolton town centre. He used to watch the contest in prison, and after his release had just six weeks to train for it. “I remember feeling this massive sense of achievement,” he says. “I’d probably say that’s one of my best performances in regards of the amount of time I trained to do it. And Darren was at the finishing line.”

At first, McAvoy didn’t tell anyone he met through training about his past life. But as rumours began to swirl around his rowing club – where had this redoubtable machine been this whole time? – people began to Google him. He decided to share his story in a blog. He initially worried about the criticism. That people would say he’d done a lot of bad things and didn’t deserve to have what he’d now got; that he shouldn’t be put on a pedestal. But he is very careful not to glamorise his past life. In 2016, his memoir was published – and he’s had many offers to turn his life story into a film. But he has always turned them down.

Apart from sport, McAvoy campaigns for prison reform. Though he feels that there are some prisoners permanently tied to a life of organised crime, “the vast majority aren’t that and I genuinely do think you can help them,” he says. As a teenager, he romanticised criminal life. “It’s a very toxic, horrible world. Once you get in it, it’s very difficult to remove yourself from it … That’s why I can relate to a lot of these kids that end up in prison for gang stuff because I understand how they can get sucked into that world. It’s very difficult for them to see anything outside that until they get to a point of growing up and maturing.”

Through his prison reform work, he’s advised the Ministry of Justice and Theresa May’s policy team at No 10. “I think prevention is better than cure,” he says. “And if you put more investment in people before they end up in prison, you’ve got a better chance to keep them out of prison.” He recalls one occasion, during a parkrun inside prison grounds, when he talked to the chair of Brentford FC, who was there on a visit. “I said to him, I could halve the criminal justice bill for young offenders. And he asked, ‘how would you do it?’. And I said, I’d send all these kids to the best private school in the UK.”

The first time he was allowed to leave the country he headed to Lake Annecy, in Haute-Savoie, south-eastern France, to do a training camp with a group of triathletes. It was the first time he’d been to the mountains. “It was the most amazing feeling ever,” he says. “I was free again. That was probably one of the happiest days of my life.”

Now, McAvoy has one motivation. “It’s quite simple, actually – it’s helping other people. I know it sounds a bit cheesy, but I’m in a very privileged position now where I’ve come from nothing,” he says. “I’d been in such a dark situation and I’ve managed to get myself out of it because I had the will, drive, determination and the mindset, but then also I had the support and help and that unlocked all of these things.”

If McAvoy wanted, he could make a decent living as a professional public speaker. Instead, most of his energy is spent working with young people on his Alpine Run Project – a six-month fitness programme culminating in the famous Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc run through the French Alps. He set up the project in 2023, with the help of various partners including Nike (which started sponsoring him in 2017 after one of its executives read about his story, and has done so ever since). It was an idea he’d had more than seven years ago: taking underprivileged kids from inner cities out on trail runs and exposing them to opportunities and Olympic athletes. He wanted them to experience a place that profoundly changed him. In the first year, 14 kids took part. This year, more than 500 have been involved. He cycles through the stories of the children he’s come into contact with through the project, and he’s fizzing with excitement as he talks about the impact the programme has had on them, and him.

You get the sense that he’s trying to be the mentor he lacked when his stepfather came into his life at an impressionable age. “I’ve got no doubt whatsoever, if I had anyone else come into my life – Richard Branson, an Olympic athlete, whoever – when I was that age, my life would have gone down a very different road.”

McAvoy’s uncle Micky died in 2023. The last time McAvoy saw his stepfather was in the reception area in Belmarsh in 2002. While being transferred, McAvoy heard his voice and called out his name. They shouted to each other and convinced the police to let them see each other. They opened his stepfather’s cell. “I remember seeing him that day in that reception area in Belmarsh. And he was handcuffed to a prison officer who was half his age,” he says. “It was very weird. Going back to when I was a kid and when I first saw him, then all the years I spent with him and all the things I was doing with him, to then see him in that situation in prison, and the way he just looked really weak. He had lost all his power. And that was the last time I saw him.” Tobin has been in prison ever since.

Does McAvoy hold any resentment or blame toward his stepfather? “No,” he says emphatically. “I know it sounds weird … but I was loved. I genuinely was. I wasn’t abused. No one ever made me do anything I didn’t want to do. Did they encourage me? I don’t think they overtly did at the beginning, but I don’t think they realised what they were doing. I think it was quite careless,” he says. “I always made a conscious decision about what I wanted to do and no one ever made me do anything.”

As for whether he has any regrets about his past, he says: “I always regret what I did because my behaviour affected other people,, but I don’t regret the 10 years I spent in prison because I feel as if I learned so much about myself. And yeah, I would go through that journey again if I had to.”

For more information go to Alpine Run Project or Instagram